One of the most persistent myths in patent education is that a patent automatically gives its owner the right to make, sell, or profit from an invention. In reality, patents work very differently. This fourth installment of the Patent Education Series clarifies what patent rights actually are, how enforcement works, and why patents are best understood as strategic tools rather than guarantees.

If you’ve ever heard someone say, “I patented it, so they can’t compete,” this article is for you.

What Rights Does a Patent Grant?

A patent grants the right to exclude others—not the right to practice the invention yourself.

In the United States, patents are issued by the United States Patent and Trademark Office, but enforcement does not happen automatically and it does not happen through the USPTO. Instead, patents provide a legal basis for action if and when infringement occurs.

Specifically, a patent allows its owner to prevent others from:

- Making the claimed invention

- Using it

- Selling or offering it for sale

- Importing it into the United States

These rights are limited in time (typically 20 years from filing for utility patents) and limited in scope by the language of the claims.

What a Patent Does Not Give You

Understanding what patents do not provide is just as important as understanding what they do.

A patent does not:

- Guarantee commercial success

- Grant permission to sell a product (other patents may block you)

- Automatically stop infringement

- Provide enforcement without cost

- Ensure broad protection if claims are narrow

Many inventors are surprised to learn that it is possible to own a valid patent and still be unable to practice the invention without infringing someone else’s earlier patent. This is common in crowded technology spaces.

Patents as Exclusionary Rights

From a legal perspective, patents are exclusionary rights, not affirmative rights. This distinction shapes everything about enforcement.

Think of a patent as a fence, not a factory. It defines a boundary in legal space. Anyone who crosses that boundary without permission may be infringing—but the fence does not build the product or run the business for you.

This framing is central to patent education because it resets expectations. Patents create leverage, not certainty.

What Is Patent Infringement?

Patent infringement occurs when someone practices every element of at least one patent claim without authorization. This analysis is highly technical and claim-specific.

Key points to understand:

- Infringement is evaluated claim by claim

- Small design changes may or may not avoid infringement

- Intent is not required—accidental infringement is still infringement

- Determining infringement usually requires expert analysis

Because of this complexity, many disputes never reach court and are resolved through negotiation or licensing.

How Patent Enforcement Works in Practice

Patent enforcement is not handled by a government agency. It is the responsibility of the patent owner.

Enforcement typically follows a progression:

- Monitoring

Patent owners monitor the market for potentially infringing products or services. - Initial Contact

This may include a notice letter or licensing inquiry rather than an immediate lawsuit. - Negotiation or Licensing

Many matters resolve through licensing agreements, settlements, or design changes. - Litigation (if necessary)

If disputes cannot be resolved, enforcement may proceed through the court system.

Litigation is expensive, time-consuming, and uncertain. For this reason, many patents are enforced strategically rather than aggressively.

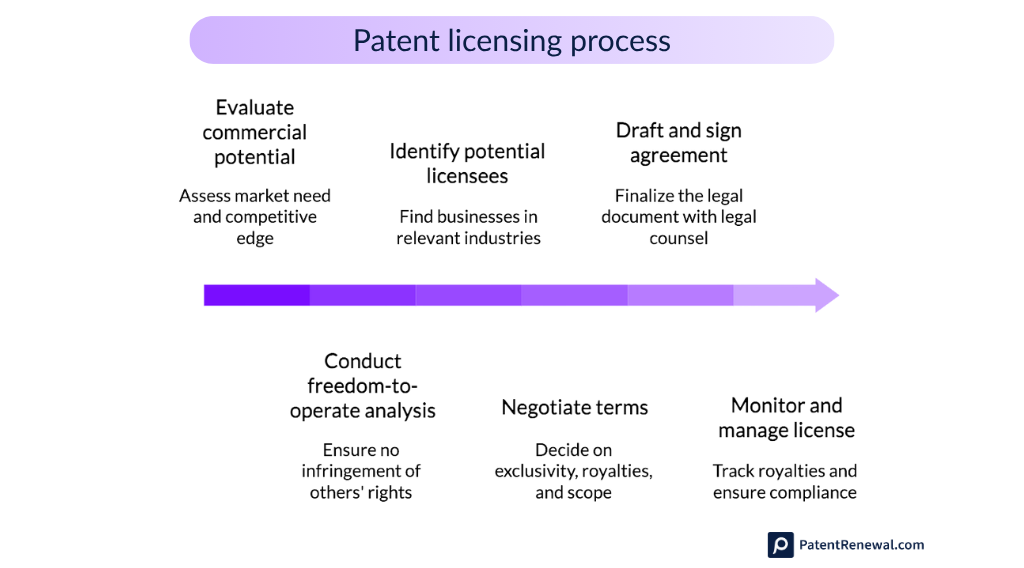

Patent Licensing: A Common Outcome

One of the most common—and misunderstood—uses of patents is licensing.

Licensing allows the patent owner to grant permission for others to use the invention under defined terms. This can include:

- Royalties

- Lump-sum payments

- Cross-licensing arrangements

- Field-of-use restrictions

Licensing is often preferable to litigation and is a core reason patents hold value in business and investment contexts.

From a patent education standpoint, licensing demonstrates that patents are not just legal instruments—they are economic ones.

Defensive vs. Offensive Patent Strategies

Not all patents are used the same way. Organizations typically adopt one or both of the following approaches:

Defensive Use

Patents are held to prevent others from asserting patents against you. This is common in technology companies that operate in dense patent landscapes.

Offensive Use

Patents are actively asserted to stop competitors or generate licensing revenue. This requires resources, planning, and risk tolerance.

Neither approach is inherently right or wrong. The appropriate strategy depends on business goals, industry norms, and available resources.

International Considerations

Patent rights are territorial. A U.S. patent has effect only within the United States.

If protection is needed elsewhere, separate patents must be pursued in other jurisdictions. Enforcement standards, costs, and remedies vary widely by country, making international patent strategy a specialized area.

Understanding this limitation is another important element of realistic patent education.

Why Most Patents Are Never Enforced

Despite their importance, most patents are never litigated. Reasons include:

- No detectable infringement

- Enforcement costs outweigh potential benefits

- Strategic value lies in deterrence or signaling

- Patents are held for future flexibility

A patent can still be valuable even if it is never asserted. Its presence alone may influence partnerships, acquisitions, and investment decisions.

Patents in Startups and Fundraising

In startup contexts, patents often serve as signals:

- Technical credibility

- Long-term defensibility

- Barrier-to-entry narratives

However, sophisticated investors understand that not all patents are equal. Claim scope, remaining term, and enforceability matter far more than the mere existence of a patent number.

This is why patent education emphasizes quality, strategy, and understanding—not just filing.

Common Misconceptions About Patent Rights

Let’s correct a few common misunderstandings:

- “I have a patent, so they must stop.”

→ Only if infringement can be proven and enforced. - “Patents automatically protect me worldwide.”

→ Patent rights are country-specific. - “If I file first, I win.”

→ Filing date matters, but scope and prosecution quality matter more.

Clearing up these misconceptions helps inventors and founders make informed decisions rather than expensive assumptions.

Why Patent Rights Literacy Matters

You don’t need to enforce a patent to benefit from understanding patent rights. Literacy in this area helps you:

- Assess real-world value

- Communicate intelligently with counsel and partners

- Avoid overconfidence or underutilization

- Align IP strategy with business reality

That is the goal of this Patent Education Series—to replace mystery with clarity.

What’s Next in the Patent Education Series

Now that we’ve explored what patent rights actually provide, the next article will focus on how people learn the patent system without becoming patent attorneys, and why patent education is valuable far beyond legal practice.

Understanding that distinction is key to using patents wisely—rather than being surprised by them later.