For many inventors and founders, filing a patent application feels like the finish line. In reality, it’s the starting gate. Once an application is submitted, it enters a multi-year review process known as patent examination—a structured, methodical evaluation carried out by the United States Patent and Trademark Office.

This third installment of the Patent Education Series pulls back the curtain on what actually happens after filing. Understanding patent examination is one of the most valuable forms of patent education because it explains why patents are granted, why they are rejected, and how outcomes are shaped by communication, not just invention quality.

The Role of the Patent Examiner

Once an application is filed, it is assigned to a patent examiner—a technically trained specialist responsible for evaluating whether the invention meets the legal requirements for patentability.

Examiners are typically engineers or scientists with domain expertise aligned to specific technology areas (called art units). Their role is not adversarial, but it is critical and exacting. They must ensure that any patent granted:

- Is new (novel)

- Is not obvious in light of existing technology

- Is clearly described and enabled

- Meets all formal and procedural requirements

This evaluation is conducted against a massive body of existing knowledge known as prior art.

What Is Prior Art—and Why It Matters

Prior art includes any publicly available information that existed before the application’s filing date, such as:

- Earlier patents and published applications

- Academic papers and technical journals

- Product manuals and documentation

- Public demonstrations or disclosures

During examination, the examiner conducts a prior art search to determine whether the claimed invention has already been disclosed—or whether it would have been obvious to someone skilled in the field.

This step is central to patent examination and a core concept in patent education. Many first-time applicants assume rejection means failure. In practice, it often means the examiner has found related material that must be addressed and distinguished.

The First Office Action: A Milestone, Not a Verdict

For most applications, the first major communication from the examiner is a document called an Office Action. This typically arrives months—or even years—after filing.

It is important to understand a key truth of the patent system:

Most patent applications are rejected at least once.

This initial rejection is normal. It reflects the examiner’s preliminary conclusions based on prior art and legal standards, not a final decision.

Types of Office Actions

Office Actions generally fall into two categories:

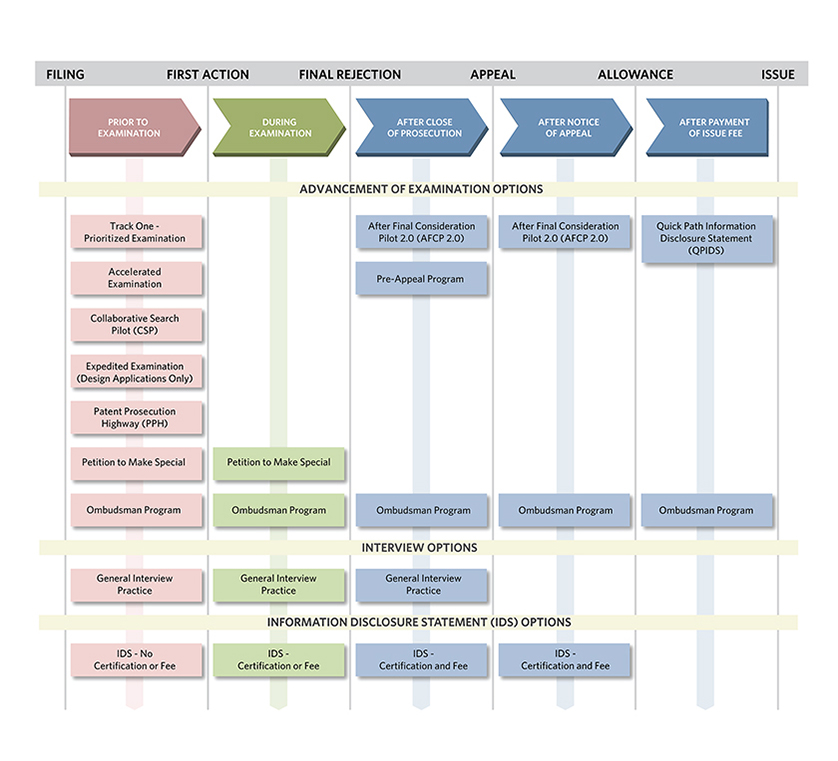

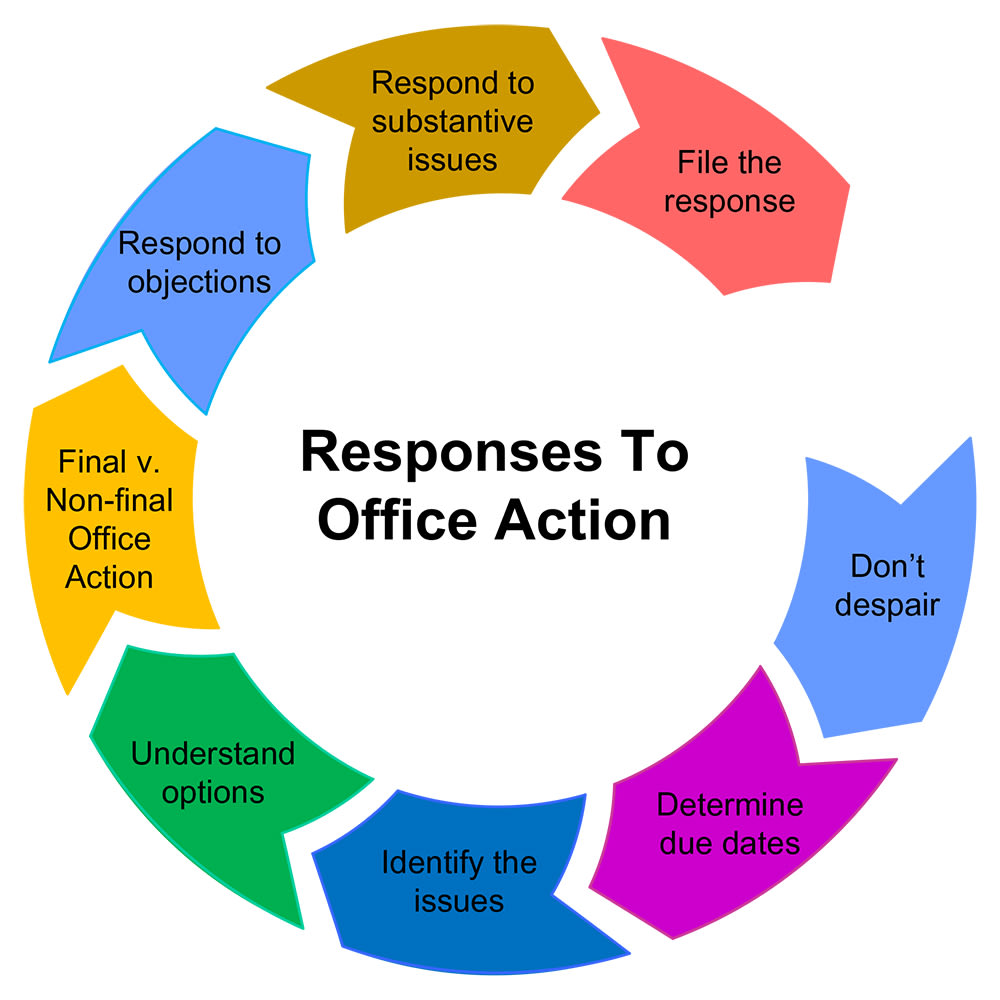

Non-Final Office Action

This is the most common first response. It outlines the examiner’s concerns and gives the applicant an opportunity to respond. These concerns may include:

- Prior art rejections

- Issues with claim clarity or scope

- Formal or procedural deficiencies

Applicants are given a fixed period to reply, typically with amendments and arguments.

Final Office Action

A Final Office Action indicates that the examiner is not persuaded by prior responses or amendments. While it sounds definitive, it does not always mean the end of the road. Applicants may still have options, including further amendments, appeals, or continuation filings.

Understanding these distinctions is essential to navigating the system calmly and strategically.

Common Grounds for Rejection (Conceptually Explained)

Patent examination relies on specific statutory standards. While the legal citations can seem intimidating, the concepts behind them are approachable.

Novelty (Newness)

If a single prior art reference already discloses all aspects of the claimed invention, the claim is rejected for lack of novelty.

Obviousness

Even if no single reference discloses everything, an examiner may argue that combining multiple references would make the invention obvious to a skilled practitioner.

Written Description and Enablement

The application must clearly explain the invention in sufficient detail. If the examiner believes the claims go beyond what is actually described, rejections may follow.

These rejections are not judgments about creativity—they are assessments of legal sufficiency.

Responding to an Office Action

A response to an Office Action is where much of the real work happens. This step often involves:

- Amending claim language

- Clarifying technical distinctions

- Explaining why cited prior art does not apply

- Narrowing claims to focus on core inventive aspects

This back-and-forth between applicant and examiner can repeat several times. Each round refines the scope of the invention and clarifies how it differs from what already exists.

From a patent education perspective, this process demonstrates an important principle: patent protection is negotiated, not declared.

Examiner Interviews and Communication

In many cases, applicants or their representatives may request an examiner interview. These conversations can be invaluable for resolving misunderstandings, clarifying intent, and identifying paths forward.

While interviews are not mandatory, they often help align both sides and streamline prosecution. They also highlight that patent examination is a human process guided by structured rules—not a purely automated decision.

Timelines and Realistic Expectations

Patent examination is not fast. Typical timelines may include:

- 12–24 months before first examination

- Multiple Office Actions over several years

- Delays due to workload, complexity, or applicant response timing

Understanding these timelines is part of responsible patent education. Patents are long-term strategic assets, not short-term approvals.

Outcomes of Patent Examination

At the end of examination, several outcomes are possible:

- Allowance – The examiner agrees that the claims meet all requirements

- Abandonment – The applicant chooses not to continue

- Appeal or continuation – The process continues through additional pathways

Importantly, allowance often comes after significant claim refinement. The issued patent may look different from what was initially filed—and that is by design.

Why Patent Examination Literacy Matters

Even if you never draft or prosecute a patent yourself, understanding examination empowers better decisions:

- Inventors gain realistic expectations

- Founders can align IP strategy with business goals

- Engineers can communicate more effectively with legal teams

- Organizations avoid costly misunderstandings

This is why the Patent Education Series focuses on how the system actually operates, not just abstract rules.

Looking Ahead in the Patent Education Series

Patent examination is where ideas meet scrutiny, structure, and law. It is not a barrier to innovation—it is the mechanism that ensures patents serve their intended purpose.

In the next article of the Patent Education Series, we’ll explore what rights a patent actually grants, how enforcement works, and why owning a patent is very different from automatically having market power.

Understanding that distinction is critical for anyone serious about innovation.